Jean Twenge’s new book “Generations” is a treasure trove of data. Leveraging 24 different data sets, some of which have collected information on American citizens since the 1940s — her work compiles and analyzes data representing a massive total of 39 million people.

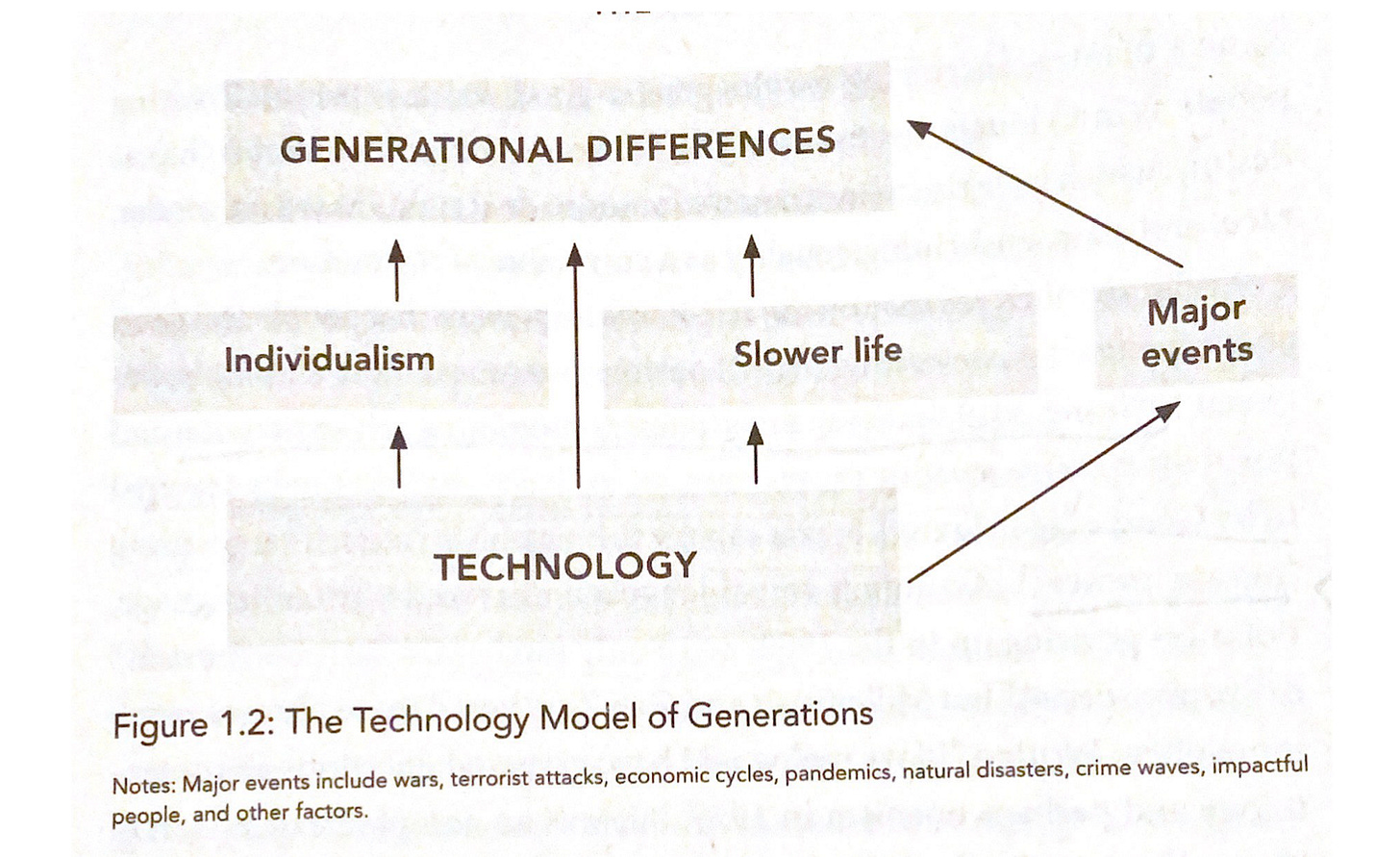

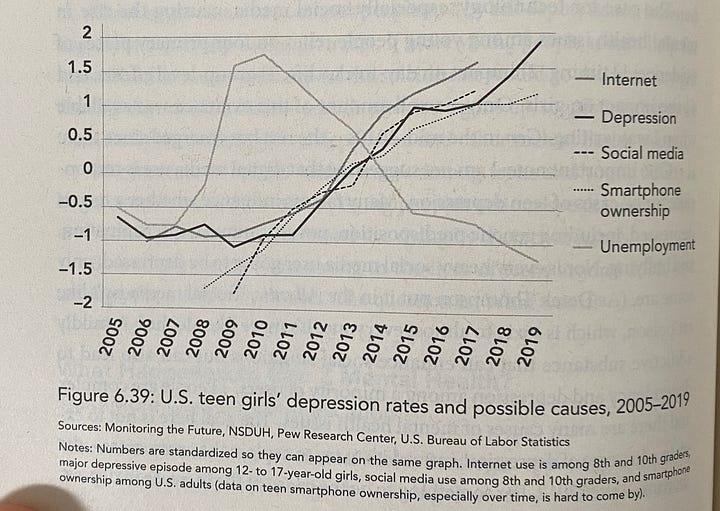

Her thesis is bold: contrary to the traditional theory that major events cause generational differences, the data reveals that “changes in technology are the underlying driver of each living generation’s unique makeup.”

To unroll the thesis further, with the increased development and expansion of technology driving the way, it also ushered in two major downstream effects: 1) a slower life strategy and 2) increased individualism.

She traces the way through all of the living generations in America today:

-the Silents, born 1925–1945

-Baby Boomers, born 1946–1964

-Gen X, born 1965–1979

-Millennials, born 1980–1994

-Gen Z, born 1995–2012

-and the still-to-be-named cohorts born after 2012

Moving from generation to generation and chapter to chapter, you can see these three influences changing the culture and experience of American life dramatically in the last 100 years [especially through the graphs in the book's chapters — these charts alone are worth purchasing Generations]. For context, Twenge opens the book with a picture of life in North Sentinel — an island that has escaped the reach of technology; thus, life and culture remain barely different than 200 or more years ago.

Twenge does much to underly that these transformations offer tradeoffs — some of these developments lean toward good, and some lean toward bad — but that generational changes don’t need to be understood in delineating them as good vs. bad. Rather, it is more about acknowledging that these changes just are what they are — that we don’t have to place them in such rigid categories — that they are grey in many ways and that it is just how life is — most often blurry and not easily categorized.

Here is the Technology Model of Generations:

First downstream effect: Individualism — technology makes individualism possible.

“Until well into the 20th century, it was difficult to live alone or to find the time to contemplate being special, given the time and effort involved in simply existing. There was no refrigeration, running water, central heating, or washing machines [which weren’t widely used until the 1940s, dryers until the 1960s]. Modern grocery stores didn’t exist, and cooking involved burning wood. Those who could afford it hired servants to do the enormous amount of work involved, but the poor did it all themselves (or were servants doing it for someone else). Daily living in those eras was a collective experience. In contrast, modern citizens have the time to focus on themselves and their own needs and desires because technology has relieved us of the drudgery of life.”

As technological progress moved our economies from focused on agriculture and household labor to information and service work, the shift from more collective living styles moved to more individualistic. Twenge writes, “Individualism can’t exist without modern technology. Every individualistic country in the world is an industrialized nation, although not every industrialized nation is individualistic.”

Individualism brought in many transformations that have shaped culture and life as we know it: the areas of the civil rights movement, Black Lives Matter, the feminist movement, the gay rights movement, and the transgender rights movement all stem from the downstream effect of individualism. These transformations are born from a theme of individualism — that everyone should be treated equally.

Individualism has also had other downstream consequences—such as the significant epidemic of loneliness in the United States.

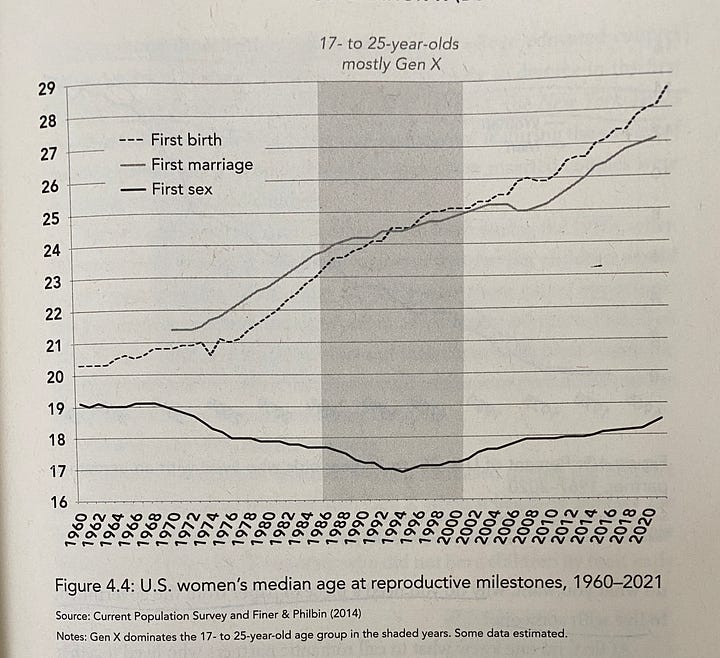

Second downstream effect: Slower Life Strategy — technology has had “an enormous impact on how we live: taking longer to grow up, and longer to grow older.”

Twenge writes:

“This trend isn’t about the pace of our lives, which has clearly gotten faster, but about when people reach milestones of adolescence, adulthood, and old age, life getting a driver’s license, getting married, and retiring.”

This downstream effect is encapsulated in the “life history theory,” as described by Twenge:

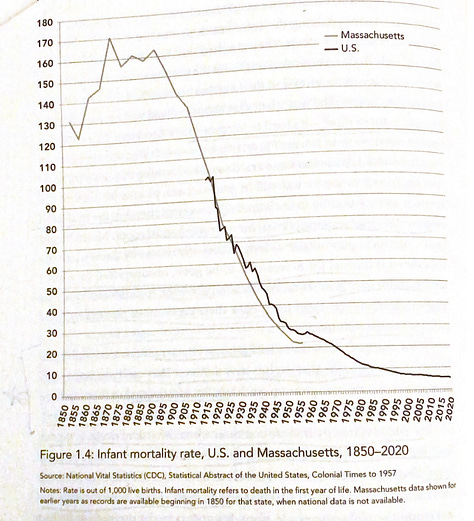

Life history theory observes that parents have a choice: They can have many children and expect them to grow up quickly (a fast life strategy), or they have fewer children and expect them to grow up slowly (a slow life strategy). The fast life strategy is more common when the risk of death is higher both for babies and for adults and when children are necessary for farm labor. Under those conditions, it is best to have more children and to have those children early to make sure that the children are old enough to take care of themselves before one or both parents die.

….

In the 21st Century, the infant mortality rate is lower, education takes longer, and people live longer and healthier lives. In this environment, the risk of death is lower, but the danger of falling behind economically is higher …. so parents choose to have fewer children and nurture them more extensively.

Here is just a sample of Twenge’s graphs that chart some of the major changes in the course of life in America over the last century or so:

What does this all mean?

I’d suggest grabbing Twenge’s book to examine her predictions for yourself, but what I will say from what I have unrolled here is that American life as we know it has changed exponentially in the last 100 years compared to the previous 100, and I would expect the same if not increasing change in the next century. If I am wrong, I would be happy to be so, as I think the rate of technological development is becoming difficult for the human animal to handle.

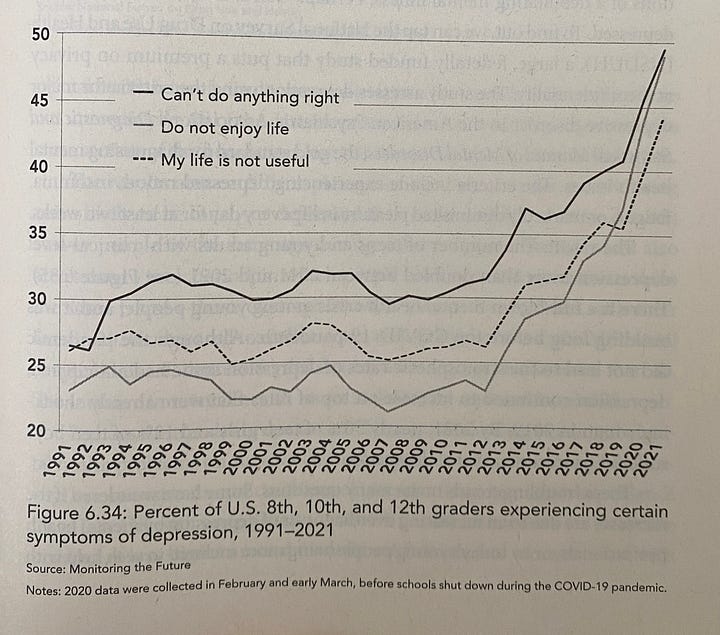

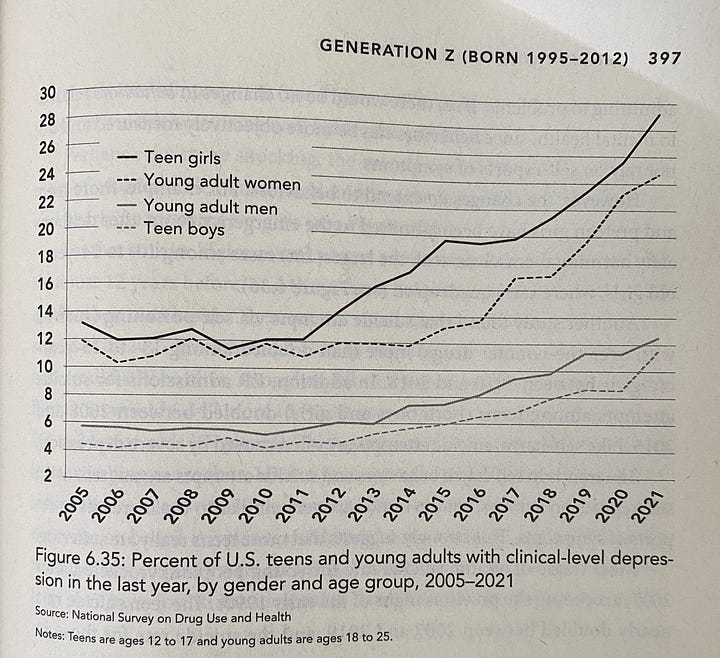

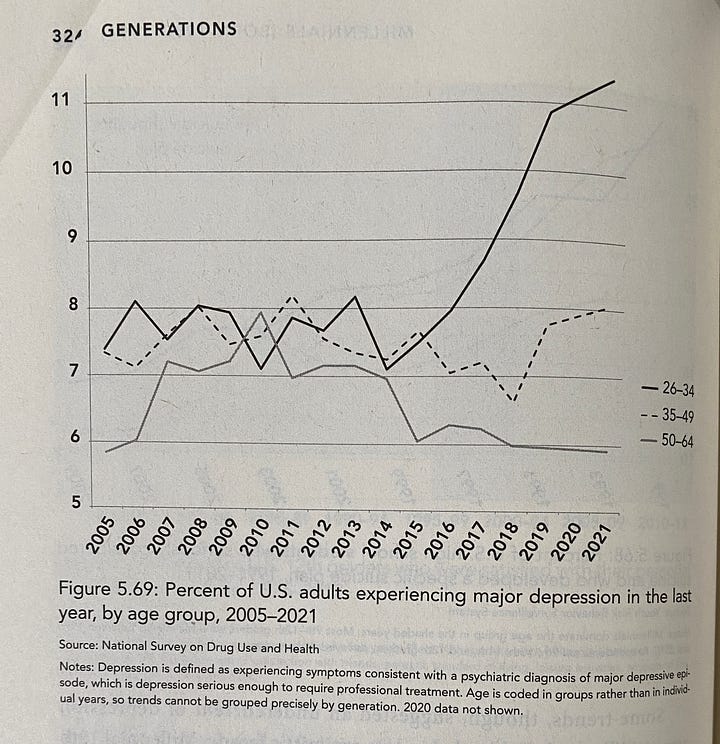

One of the more negative downstream consequences that I have detailed in previous posts is the increasing rates of mental health problems. This is manifesting in all of the generations (except the Silents — which, even though most likely to die during the COVID-19 pandemic, remarkably had the least consequences in terms of mental health).

Change is happening so quickly that we lack time to reflect and gain context in our new world. Students of history can see how rapidly these changes are occurring relative to our ability to adapt — both to life and new waves of culture — but the number of the next generation interested in becoming historians is on the decline.

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress administered by the Department of Education. About 40 percent of eighth graders scored “below basic” in U.S. history last year, compared with 34 percent in 2018 and 29 percent in 2014.

Just 13 percent of eighth graders were considered proficient — demonstrating competency over challenging subject matter — down from 18 percent nearly a decade ago.

In contrast, TikTok stars are on the rise, but encapsulating or considering the context of change in human history and experience in a 42-second video (currently the average length of a video on TikTok) is much more difficult than the attention required to study and understand something deeply and produce an insightful thesis supported by a mountain of data as Twenge has done here.

The Surgeon General's Warning

On May 23rd, the Surgeon General’s Advisory released a warning. An advisory from the Surgeon General is reserved for significant public health challenges that require the nation’s immediate awareness and action. Its purpose is to call the American people’s attention to an urgent public health issue and provide recommendations for addressing it.

Dr. Jean Twenge, Prognosticator

Six years after pinpointing the looming mental health crisis now engulfing American high school and college students, Jean Twenge is at it again. This time, though, she is looking at patterns across all generations. Here is how, in her own words, Twenge

I'm a huge fan of your writing, Erin. Now I will have to read Twenge's book. You probably won't like hearing this (and the media hates Hawley), but this post reminds me a lot of another book I'm reading right now out of curiosity, which is "Manhood" by Josh Hawley. Hawley has written a lot on Big Tech previously, and he postulates that Americans need to 1) return to the Judeo-Christian roots that previously shaped our communal societies, 2) remember our own family histories (as a means of understanding oneself), and 3) put away technology, in order to sustain a socially healthy society. His book is very heavy on interesting historical references, too.