We pulled into the driveway of an aging Hawaiian couple — natives to the island for several generations. In their breezeway, the couple sold shaved ice and banana bread to captive passersby. They lived a mile or so in on a treacherous one-lane road that traced the northwestern edge of the island of Maui. On the side of the shaved ice machine, they had posted a sign that read:

“I fear the day that technology will surpass our human interaction. The world will have a generation of idiots.” The quote was attributed to Albert Einstein.

Interesting, I thought. I had never come across that quote before … and with a little research, it turns out that Einstein didn’t actually say this, but the point was well taken.

I recently finished David Brooks’ wonderful book How to Know a Person, where Brooks poses a variation of the point made by the poster on the side of the ice machine. Brooks argues that technology, the chief driver among the downstream transformations of our culture, has surpassed human interaction — but that the idiocy is one of overlooking and undervaluing the most important thing that makes human life special — relationships. And that overlooking and undervaluing diminish our individual abilities to see one other, to be sure — but taken together, en mass, leads to a lonely, agitated culture, one prime for falling apart.

He writes:

“The real act of, say, building a friendship or creating a community involves performing a series of small, concrete social actions well: disagreement without poisoning the relationship; revealing vulnerability at the appropriate pace; being a good listener; knowing how to end a conversation gracefully; knowing how to ask for and offer forgiveness, knowing how to let someone down without breaking their heart; knowing how to sit with someone who is suffering; knowing how to host a gathering where everyone feels embraced; knowing how to see things from another’s point of view.

These are some of the most important skills a human being can possess, and yet we don’t teach them in school. Some days it seems like we have intentionally built a society that gives people little guidance on how to perform the most important activities of life. As a result, we are lonely and lack deep friendships.

The humanities, which teach us what goes on in the minds of other people, have become marginalized. And a life spent on social media is not exactly helping people learn those skills. On social media, you can have the illusion of social contact without having to perform the gestures that actually build trust, care, and affection. On social media, stimulation replaces intimacy. There is judgement everywhere and understanding nowhere.

In this age of creeping dehumanization, I have become obsessed with social skills: how to get better at understanding the people right around us. I’ve come to believe that the quality of our lives and the health of our society depends, to a large degree, on how well we treat each other in the minute interaction of daily life.

All of these different skills rest on one foundational skill: the ability to understand what another person is going through … what lies at the heart of any healthy person, family, school, community organization, or society is the ability to see someone else deeply and to make them feel seen.”

How to Know a Person is a deeply thoughtful, touching, humanizing book. A broad view of Brooks' thesis is that to know another person deeply and to be deeply seen is one of the greatest gifts we can have in our lives. It also requires skills we don’t often teach, aren’t naturally always very good at, and in our technologically mediated lives — have become increasingly difficult to practice.

Brooks lays out steps for becoming a person who is better at knowing others. These are skills we can learn, teach, and practice.

A few weeks ago, my wife and I attended a dinner party. I had just finished reading How to Know a Person and was conscious about the night as an opportunity to practice what I had learned.

I am typically not long for small talk — I like to get to the heart of a conversation, and Brooks makes some strong suggestions for questions that move a conversation from small talk to one that fosters the participants coming to know each other more deeply.

First, ask humble, open-ended questions. These questions are the opposite of the kinds of questions that are judgmental in nature, such as: Where did you go to college? What neighborhood do you live in? Instead, ask questions that open with: “How did you…,” What’s it like…,” In what ways…,” and (my favorite) “Tell me about…”

One that I landed on that evening as we chatted about family dynamics was, “What was your family like growing up?”

That question took us on a long and unexpected journey. We shared stories about our parents, how much we had changed since we were young, and how we stayed the same. We talked about the kinds of people we aspired to be as we grew into adulthood.

As the night went on, some of our dining companions departed for the evening, including my wife, who was depleted after a couple of particularly early and emotionally demanding shifts in the Emergency Room.

One of Brooks’ best chapters is about how we sit with those in despair. In the book, Brooks is referring to the moments when we have the chance to show up for our loved ones — our friends in the family — when they have experienced a loss. This is a skill that my wife is especially gifted at (and that, for me, is a work in progress).

When it comes to knowing another person quickly, Lauren often finds herself at the intersection of the worst moments of people’s lives. The moment when someone finds out they are likely going to die of cancer they didn’t know they had, the moment someone finds out their child or spouse has died, the moment someone comes to realize they might never walk again. She is comfortable in moments that scare many of us.

As we approached the hour when the time came to either make our way home or linger late into the night. In the spirit of knowing a person deeply, our hosts pulled out a game created by the indomitable Esther Perel — Where Shall We Begin? A Game of Stories.

I knew it would be a late night.

If you are searching for a tool to help you practice posing open-ended questions — the ones Brooks contends are our best chance to know one another — look no further than Perel’s card deck.

Six of us remained around the table; we shuffled the cards and began.

As we took turns, each person offered vulnerability and shared stories we had never heard; we laughed, cried, and tried to puzzle out the troubles we faced. We all left the night knowing each other more deeply and loving each other more wholly.

As I have reflected on that evening since one thought has stuck with me.

That seeing someone deeply is really to be with someone in their vulnerability.

It is when we bare our fragility, mistakes, failures, and insecurities and find on the other end the response is — I see you, I still love you, I still want to be with you. In fact, as I see you more wholly, I love you even more — that we really come to be known and can know one another.

And this, to Brooks’ point, is why social media will never offer us the kind of connection that leads to this profound way of being with other people.

In 2013, Americans spent an average of six and half hours per week with friends; by 2021, that number dropped to 2 hours and 45 minutes — a 58% decline. Over the course of a year — that equates to a loss of eight 24-hour days spent with friends.

What I know most about the mind is that it is malleable with repetition and practice — and 11,520 fewer minutes a year spent on training our minds to see other human beings with the fullness and compassion — the kind that in-person interaction demands — will begin to take a toll very quickly.

This loss of in-person interaction is the reason we see statistics like between 1999 and 2019, American suicide rates increased by 33%, and from 2009 to 2021 — the number of teens who report “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” went from 26% (2009) to 37% (2019) and 44% (2021).

What I also know is that the results from the long-term studies done on overall life satisfaction show over and over again that the most important factor to our happiness throughout our lifetimes is the depth and quality of our relationships.

And all relationships are formed through a series of small interactions. Brooks refers to this process as accompaniment. I like that term. It is the process that precedes our ability to pose the kinds of questions I described at the dinner party — the part of a relationship that sets the stage for deeply seeing. It is the process of being around another person and getting a feel for them — our unconscious (and sometimes also conscious) mind is gauging energy, temperament, and manner.

In high school, my favorite part of the day was the passing periods. Seeing other people in the hall, catching up. It was these in-between moments of accompaniment. As a teacher, after the widespread adoption of the smartphone in 2011 — I noticed how much less chatter filled the hallways. Students just walked through the halls looking down at their phones — how many small opportunities that could have led to real connection were lost in the last decade or so? It is hard to calculate.

As a parent, I have the chance to pick my kids up from school. As an adult, it has been those moments — on the playground waiting for our kids to come out that I have met some of my closest friends. I could have spent those minutes scrolling on my phone or checking email, but instead, I spent them in accompaniment, and my life has been better for it.

With virtual school, virtual work, virtual lives, these small moments, the opportunities to turn accompaniment into real connection have become fewer and fewer.

If we want to find relationships where we can bare our souls, we first have to make eye contact on the playground.

Keep looking for connection,

Recommendations:

What I am Reading:

How to Know a Person by David Brooks

The Organized Mind by Daniel Levitin

Oath and Honor by Liz Cheney

What I am listening to:

The Neuroscience of Why We’re Susceptible to Lies, Outrage, and Fascism with Cass Sunstein Harvard professor and coauthor of the forthcoming book, Look Again, joins Offline to discuss the dangers of habituation. When things become so commonplace that they blend into the background of our everyday lives, we stop appreciating the good and identifying the bad. Jon and Cass examine how authoritarian regimes are normalized, whether you can pay people to quit their social media addictions, and why repeating lies makes them more believable.

Secrets to Successful Professional Relationships — Kara Swisher, Scott Galloway and Esther Perel

How Machines Learn

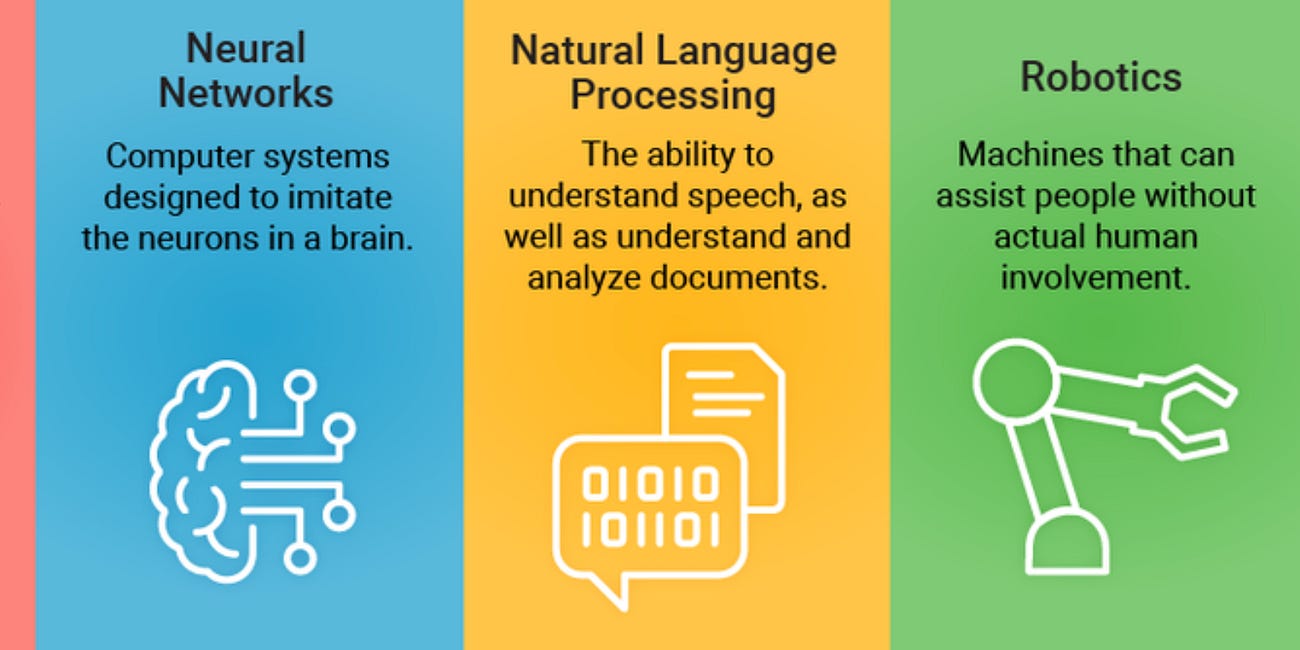

I recently had the opportunity to present at the ScalePoint conference hosted by Washington University about how our company is integrating AI into our work. After the presentation and a few discussions, I thought the presentation would make for a good article —

Solutions in 2024

I believe our ability to shape our own destiny (the extent to which we have free will) operates at three levels. First, is what I will call the macro-structural level. We can look at these as governing bodies and large-scale institutions whose policies ultimately shape individual choices and interactions. Our ability to mobilize movement in these organi…