A friend recently asked, “So, really, how Luddite are you?”

I wish my answer could be, yes, I’m totally off the grid. This substack is a case in point that I am decidedly not. I have a smartphone, use a computer most days, and work for a tech company. I’m well-versed in the age of technology, but I am also well-versed in the models of manipulative design that underpin most of the technology we interact with. So the word Luddite is an interesting one — in both its contemporary connotation, the legend of the Luddites, and the truth behind the myth.

Perhaps it’s time to unpack the term.

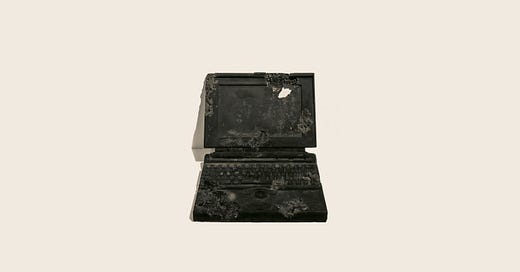

Using “Luddite” embodies resistance to embracing technology without considering the economic models that shape those products. Our current technological landscape is one where a few companies exercise almost complete control over our information—and the current incentive structures cause real harm to individual people and our collective society. Using the word Luddite is to make a point of caution against embracing platforms, such as social media, which have unleashed an unbelievably corrosive discourse, tribalism, rage, anxiety, and depression into American culture at scale. A contemporary Luddite demands we give more thought to the experiments we run on our collective minds.

In the 21st Century, “Luddite” is sometimes used disparagingly or, more often, in jest as a term for someone who dislikes new technology. I felt it was time to reclaim the word in honor of the real history of the Luddites.

In the early 19th century, the Luddites were part of a labor movement that railed against how manufacturers, adopting new technology in tandem with unskilled laborers, undermined the skilled craftsmen of the day.

The term Luddite had staying power, as the group banned together in a kind of Robinhood gang to destroy the machines that sought to replace their skilled labor. However, in his piece, What the Luddites Really Fought Against, writer Richard Conniff argues that the Luddites were not simply technophobes who wanted to smash any technology they could get their hands on. There was a method to the madness.

The Luddites themselves “were totally fine with machines,” says Kevin Binfield, editor of the 2004 collection “Writings of the Luddites.” They confined their attacks to manufacturers who used machines in what they called “a fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labor practices. “They just wanted machines that made high-quality goods,” says Binfield, “and they wanted these machines to be run by workers who had gone through an apprenticeship and got paid decent wages. Those were their only concerns.”

…

[The] people of the time recognized all the astonishing new benefits the Industrial Revolution conferred, but they also worried, as Carlyle put it in 1829, that technology was causing a “mighty change” in their “modes of thought and feeling. Men are grown mechanical in head and in heart, as well as in hand.”

…

Getting past the myth and seeing their protest more clearly is a reminder that it’s possible to live well with technology—but only if we continually question the ways it shapes our lives. It’s about small things, like now and then cutting the cord, shutting down the smartphone and going out for a walk. But it needs to be about big things, too, like standing up against technologies that put money or convenience above other human values. If we don’t want to become, as Carlyle warned, “mechanical in head and in heart.”

There is no question that technological progress is a wonderful thing. It can make our lives easier and offer new possibilities for learning or entertainment. I enjoy the benefits of traveling, Netflix, and Google Maps (although Google is scraping my data as I use it) just as much as the next person.

My Ludditeness is a posture or skepticism toward technology designed to maximize profit at the expense of democracy, discourse, and mental health. The grinding capitalistic approach, absent any sensible regulation, mines us for our data while feeding us content that brings out the worst of human nature.

These products of technology are worth taking a stand against.

Backpacking with Saints

Tomorrow, I have the opportunity to sit down with writer and scholar Belden Lane of Saint Louis University for an episode of a podcast series my friend Kelley and I have been working on. Lane is the author of several books, including, “The Great Conversation” and “Backpacking with Saints: Wilderness Hiking as Spiritual Practice.”

Our conversation tomorrow is about the power of awe, which also happens to be the topic of the new book, “Awe” by UC Berkley professor Dacher Keltner.

What Keltner and Lane both have to offer in their writings is that the power of awe is found not in technological spaces but rather in natural ones.

As Keltner writes, when I ask people where they have experienced awe? No one ever says “The Internet.”

Keltner sought to find an answer to the age-old question—how can we live the good life? “One enlivened by joy and community and meaning that bring us a sense of worth and belonging and strengthens the people and natural environments around us.” His answer: find awe.

Keltner conducted a variety of studies across thousands of participants worldwide to create a taxonomy of awe or the eight wonders of life. They are:

Other people’s courage, kindness, strength, or overcoming

Collective effervescence (when we feel a part of a “we”)

Nature

Music

Visual design

Spiritual and religious awe

Stories of life and death

Epiphany

The Luddites would approve.

What Keltner is describing is being present in moments of life that require us to be attentive, be quiet, and be small in the presence of something bigger than ourselves. To open ourselves to the possibility of being awed. Experiencing awe requires us to look up from our smartphone and out into the world teeming with possibilities, adventures, ideas, and amazing, interesting people.

To this point is a kind of carpe diem. The Dalai Lama recently gave some pretty wise advice in a new children’s book. Including this:

There are only two days in the year that nothing can be done.

One is called Yesterday, and the other is called Tomorrow.

Today is the right day to love, believe, do, and mostly to live positively to help others.