I started writing this piece still in the rhythm of summer — with the stillness of wild landscape fresh in my mind. Now, we are a week and a half back into the throws of a new school year, and our house — full of both human and non-human animals — has turned into the normal mode of chaos.

In the grind of the daily to-do list, stillness can be hard to come by. And yet, it is in those spaces — the chaotic spaces — that the lessons of stillness learned in those wild spaces are most essential to apply.

How do we find the space and time to think with clarity? The space we know is crucial for distilling the unimportant from the important.

Our challenge is the practice of holding stillness, which we know is essential for restoring the quality of our lives. Often, stillness is fleeting, as all things are fleeting. As Eastern philosophy has long known, the only constant is change. So, we must hold everything loosely.

In a season of life marked by a swirl of daily chaos, having the time to step outside of the churn and see with new eyes is both a luxury and a necessity. It reminds us that new eyes are always available to us if we can learn to call on them—that stillness is a practice as much as a place.

On a recent trip to the Sonoran desert, I was reminded of the stillness certain places demand of your senses—a stillness that is not to be ignored—one that is everywhere in a landscape.

The desert landscape has always been able to call me to stillness. A vast, open stretch of rock and sand in the summer heat crushing the body “into a lizard state of mind,” so says the great writer Terry Tempest Williams.

How can anything survive? And yet, it does.

The Sonoran desert, in particular, teems with life. Cacti, a hundred years old, four times your height, and a night so dark the stars are a blanket — the desert constantly calls us to smallness — to stillness.

Yet, how do we find more stillness — how do we cultivate a practice, a habit of creating a space for equanimity? How do we maintain inner calm and steadiness regardless of external circumstances?

In Buddhist teaching, we learn that humans often relate to our experiences through a lens of craving, attachment, or aversion, all of which increase suffering. Buddhists understand equanimity as an antidote to all these – as “a balanced reaction to joy and misery.”

Enough

One of the principal ways to find equanimity is to understand in your mind, body, and soul that what you are and what you have is already enough. This is especially true in our material culture.

Epicurus: “Nothing is enough for the man to whom enough is too little.”

In a time when all the material possessions in the world are constantly pushed into our consciousness — telling us what we must have to be “this or that kind of person” — it is easy to lose sight of the riches we already have.

There is a great story of a conversation between the famous writers Joseph Heller and Kurt Vonnegut. They were once at the same party, the party of an ostentatious billionaire.

Vonnegut turns to Heller and says — “Joe. How does it feel that our host only yesterday may have made more money than your novel has earned in its entire history?”

Heller replies — “I’ve got something he can never have.”

Vonnegut — “And what on Earth could that be?”

Heller — “The knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

Hold everything loosely. There is a famous saying — that"you cannot step into the same river twice." In order to find stillness we have to remember that everything is always changing. Nothing is permanent. To see the moment for what it is — one that will never happen again — at least not ever quite the same way. The next time we will be older, wiser, more haggard.

So when we can hold the chaos loosely, when we can step outside the moment and observe it, this is where we can find stillness.

We can find stillness in our gratitude for the chaos that will never happen quite the same way again.

New Podcasts are Out!

We have had some excellent discussions lately with a wide range of interesting guests! See below for the latest.

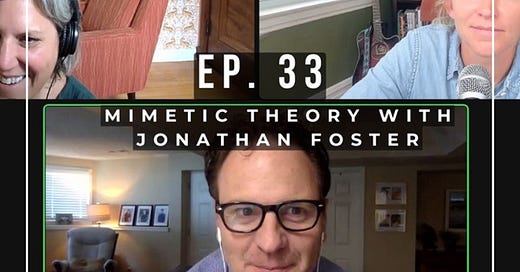

Dr. Jonathan Foster joins the (A)Theist Podcast to help hosts Kelley and Erin learn about Mimetic Theory, an explanation made by philosopher René Girard. Mimetic theory posits that human behavior and culture are driven by desire, and that desire itself is driven my what we see in others and wish to imitate (or "mimic").

We recorded this interview with Thomas Jay Oord several weeks before releasing it. You'll hear references to a trial in which members of the Church of the Nazarene have charged Dr. Oord with promoting doctrines out of harmony with the doctrinal statements of the Church. This accusation and trial are the result of Dr. Oord's continued affirmation of LGBTQ+ individuals.

********

Thomas Jay Oord is a theologian well known for his scholarly work researching love, open theism, process theism, the relationship between religion and science, and most relevant to this episode: Open and Relational Theology. This concept posits that God gives and receives in relation to creation. In other words, that God is a powerful force, but not necessarily all-powerful in the way many religions claim.

Open and Relational Theologists come from many different religions and denominations - Christian, Buddhist, Jewish, Muslim, Pagan, Spiritual but not Religious, and many more. It’s a fascinating cross-section of religious scholars!

Thomas Jay Oord has published many books and is a prolific blogger. Be sure to check out his work here: www.thomasjayoord.com. You should also check out www.c4ort.com for more information about Open and Relational Theology.

Alcoholics Anonymous is a well-known fellowship of people dedicated to the abstinence-based recovery from alcohol addiction. While the 12 Step program is deeply based in spirituality, the organization is non-denominational and open to anyone regardless of faith.

Erin and Kelley invite David to the show to discuss his experience working the 12 steps, even as someone who has a complicated history with traditional Christian theology. David articulates the idea that AA has essentially taken the very best of all religions, neutralized the organized religion part, and given people the ability to create their own form of higher power. For many, this process has led to lifelong recovery from an otherwise debilitating disease.

Recommendations

What I am reading:

I am revisiting two good ones from Ryan Holiday — Stillness is the Key, and The Obstacle is the Way

Mating in Captivity by Esther Perel

Remote: Office Not Required By Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson