The Proximity Principle

How technological mediation both extends and diminishes our proximate zone for friendship.

*Author’s Note: If you frequently follow this space, you may have noted that this edition of the Missives is coming out a few days late. I’ve been on the road with my wife and daughter this past week, exploring the Michigan sand dunes, and our reentry to the real world has been back-to-back with events and baseball games. But all those adventures inspired this week’s topic: The Proximity Principle. I hope you enjoy it. And if you do, please feel free to pass it along to a friend—it might even bring you closer.

"Wishing to be friends is quick work, but friendship is a slow-ripening fruit."

—Aristotle

"Friendship is the currency of the soul. It is a treasure that enriches our lives, expands our perspectives, and nourishes our hearts."

— Maria Popova

The friendships we develop and sustain as we move through life are one of the great joys of living. And while it may seem obvious that we become friends with people we meet. It is an idea worth exploring: How do we come to know one another? And how does proximity shape our friendships?

The earliest study of the proximity principle, also known as the propinquity effect, can be traced back to the 1950s. The pioneering research on this topic was conducted by social psychologists Leon Festinger, Stanley Schachter, and Kurt Back in 1950 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

In their study "The Spatial Ecology of Group Formation," Festinger, Schachter, and Back examined friendship formation patterns among MIT students living in married student housing. They found that the physical proximity of individuals significantly influenced the likelihood of forming friendships. Specifically, they discovered that individuals living in close proximity, such as in the same building or floor, were more likely to become friends than those living further apart.

This landmark study laid the foundation for understanding the impact of physical proximity on social relationships and demonstrated the significance of proximity in initiating and fostering interpersonal connections.

Eleven years later, social psychologist Theodore Newcomb published "The Acquaintance Process," which further expanded the understanding of the proximity principle and its influence on friendship formation. Newcomb aimed to investigate the factors that contribute to the development of friendships.

In the study, Newcomb examined a group of male college students living in the same dorm. He examined housing arrangements, roommate assignments, and floor plans to determine the level of physical proximity among the students. Additionally, he surveyed the participants on their attitudes, interests, and opinions to assess their similarities and differences.

Newcomb found that individuals who lived in close physical proximity, such as on the same floor or adjacent rooms, were more likely to form friendships than those living further apart. The study highlighted the role of mere exposure and familiarity in shaping social relationships. The more frequently individuals encountered each other due to physical proximity, the greater the opportunity for interaction and the development of liking and rapport.

How much time does it take to develop this kind of rapport? University of Kansas professor Jeffrey Hall’s research suggests that, on average, very close friendships tend to take around 200 hours to develop— or about 50 four-hour dinner parties.

It appears this is the sweet spot for developing friendships. You can grow a relationship if you have similar interests and compatible personalities and pass through each other’s proximal zones with enough frequency. The trouble is many of us are missing opportunities for engagement because we are paying more attention to our devices than the people around us.

Virtual Proximity, Emotional Distance

For Aristotle, friendships were essential for human flourishing and the cornerstone of a well-functioning society.

Aristotle also recognized that proximity plays a crucial role in friendship formation. Regular face-to-face interaction allows individuals to get to know one another, build trust, and engage in activities together. Physical proximity facilitates the mutual exchange of emotions, ideas, and experiences, thereby strengthening the bonds of friendship.

"For without friends no one would choose to live, though he had all other goods." and "And if the existence of friends is most necessary for life, then it is evident that they are needed for the good life." — Aristole, Nicomachean Ethics

But Aristotle's perspective primarily focused on physical proximity and the importance of in-person interactions. What would Aristotle make of our modern technological communication, which enables people to connect across great distances?

Do our new digital villages result in the same kind of trust that is built in physical ones? Are the quality and kind of emotions, ideas, and experiences exchanged online as deep and meaningful as those in person?

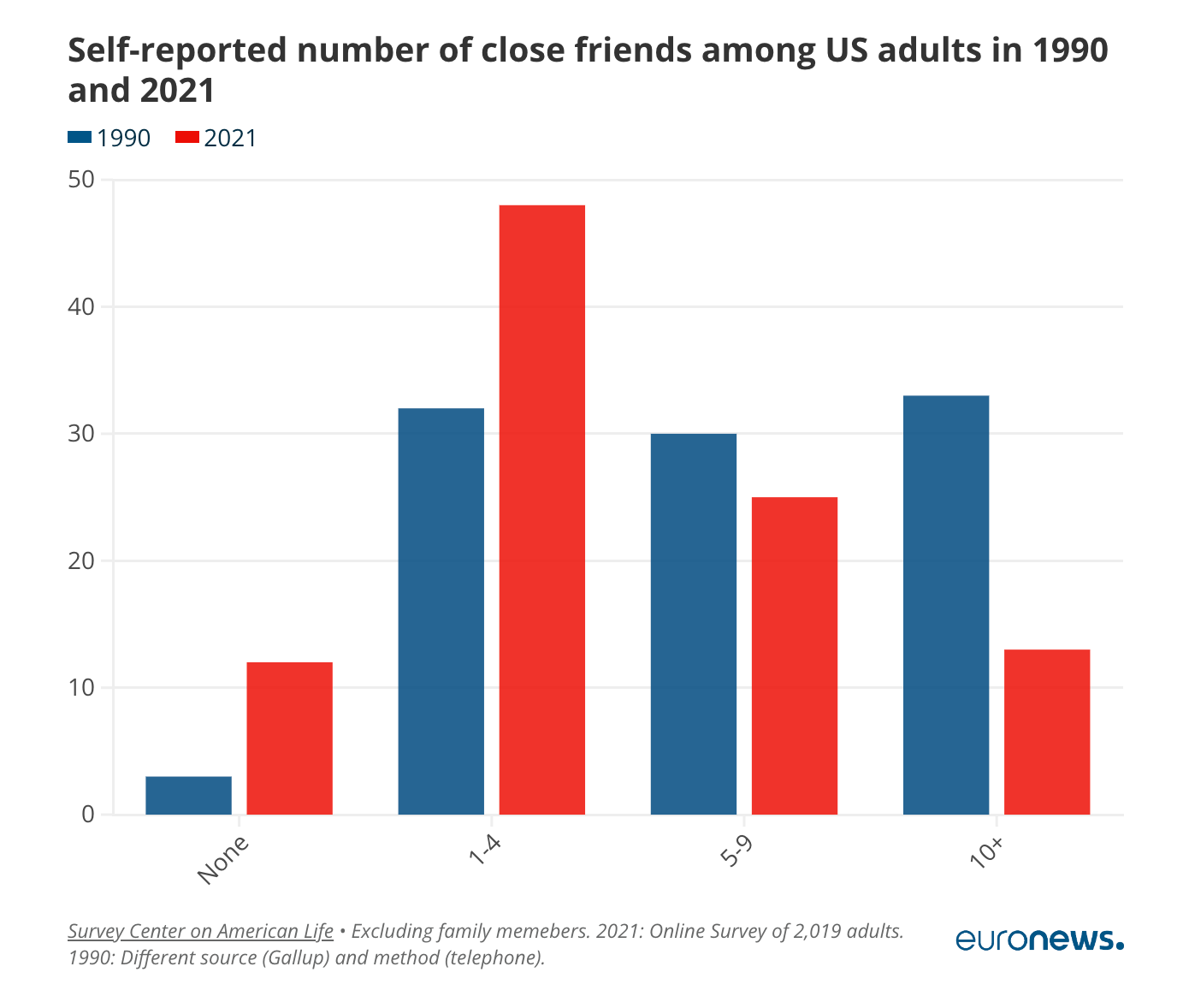

Most of the research indicates that the answer is no—that while our new digital overlay does allow us to stay connected with an unlimited number of contacts from our past and present, the result is shallow connections — that the vast number of online connections facilitated by social media can result in a larger network of superficial relationships, which can dilute the depth and intimacy leading people to have many acquaintances but fewer close, meaningful connections.

Or, as Professor Scott Galloway would say, “You have friends without friendship.”

(I highly recommend MIT professor Sherry Turkle’s writing on this subject. Her book “Reclaiming Conversation” about the healing power of in-person conversation, is especially good, and very much to Aristotle’s point.)

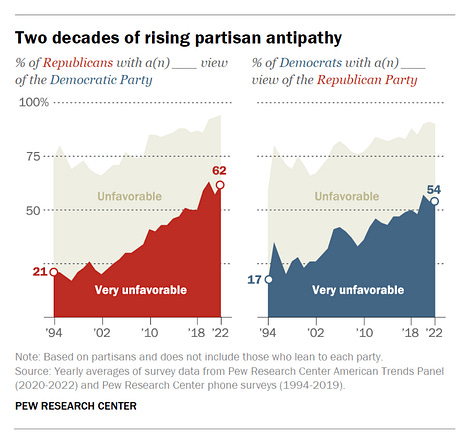

Our collective society also seems to be struggling with virtual discourse as our primary pathway for interaction. Several studies from the last decade show that smartphones and social media have corrosively affected our discourse and attitudes toward one another as American citizens. Here are a couple:

The added fact that Americans tend to live in homogenous communities and often no longer speak to or know the neighbors that they do live near, I suspect, contributes to these hostile and disconnected feelings.

Life's Time Limit

Another suspicion I have is that our ideas around finitude, resulting from the digital universe, increasingly leave us with the false impression of infinite choice.

As Oliver Burkemann argued in 4000 Weeks — it is, in fact, the “finitude” that bestows our choices with meaning.

When you realize that you only have 4000 weeks on this planet, the 200 hours (or 50 dinners) it takes to develop a meaningful friendship shifts into focus.

Our location — in time and space — puts us in proximity and opportunity to develop many friendships throughout our lives — but it is the proximal relationships that we lean into, that we decide to nurture, that we choose to give some of our 4000 weeks to, are those that will offer warmth, dimension, and interest to our lives.

And an important point that took me a while to recognize is that those proximal zones don’t last forever. They will shift and move with different chapters of our life, so when you find a potential new friend in your proximal space, now is the time—because we are never guaranteed tomorrow.

Capitalism is Eating Everything, Including Your Attention Span

“Capitalism has no land left to cultivate but the self. Everything is being cannibalized — not just the goods and labor, but personality and relationships and attention. The next step is complete identification with the online marketplace, physical and spiritual inseparability from the internet:

Great analysis and so interesting. I heard a podcast a while back on the proximity principal (I think there is a book, too), and it really influenced my parenting.... "your vibe shapes your tribe" and "you become like the five people you spend the most time with"-- I tell my kids again and again. We limit social media quite a lot, especially as you really never know who you are interacting with without being face to face.