The Shallows

What the science of neuroplasticity and Nicholas Carr have to teach us about how the Internet is shaping our minds

Author’s Note: As many of you know, I have been working on a book since last spring. I plan to use this space to work through some of the book's themes and test new material with a new post each Friday. If you have any thoughts, suggestions or recommendations, please send them to missivesfromaluddite@gmail.com. Also, please feel free to share with those who might find the work interesting!

__

“It isn’t an overstatement to say that progress has its own logic, which is not always consistent with the intentions or wishes of the toolmakers and the tool users. Sometimes our tools do what we tell them to. Other times, we adapt ourselves to our tools’ requirements.”

- Nicholas Carr, The Shallows

In 2010, Nicholas Carr published The Shallows: How the Internet is Changing the Way We Think, Read and Remember. I stand amazed, looking at the print date on his book. How could he see so clearly what the rest of us our now just catching up to? The Shallows was built as a further fleshed-out argument spawned from Carr’s 2009 piece in The Atlantic entitled Is Google Making Us Stupid? As I consider the state of our culture and collective thinking in 2023, I think the answer to this question is yes.

Carr draws on the old media theorist's idea “the medium is the message” to shape his argument about how the Internet and homo sapien neuroplasticity are engaging in concert with each other to transform the minds of 21 Century human beings. Coined by Marshall McLuhan in the 1960s, “the medium is the message” is important to understanding how every new technology transforms the human mind and influences the things we think about and how we think about them. Each medium creates a kind of construct for what we can think about. Another famous saying — from one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century Ludwig Wittgenstein “the limits of the language are the limits of my world,” works similarly. Each technology is a kind of language. It is not simply a passive vessel through which information is passed. The vessel itself shapes the idea. The structure of the tools we use to communicate shapes the message itself. Depending on the structure of the medium, the medium not only influences the development of the message but can limit the depth and nuance present. Such is communication in the age of social media, a medium that mostly flattens thinking, nuance, and empathy.

First, unpacking the concept of neuroplasticity is essential for understanding how the medium as the message works on a neurobiological level.

Until 1983, the majority of the scientific community believed the minds of mature primates were essentially fixed, that once you left childhood and adolescence, your brain was essentially done changing and growing. This idea is referred to as a fixed mindset in the educational world (this morning, my children were discussing the difference between growth and fixed mindsets on the way to school, which indicates how far this concept has evolved). To be fair, some scholars argued against this point of view decades earlier, but they were in the minority and not broadly taken seriously.

The research of one psychologist at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Michael Merzenich, blew open the door to the idea that our minds are never fixed and that our brains can change, grow, and make new connections throughout our lifetimes.

Merzenich was studying brain mapping and using microelectrodes to create the most detailed map of the primate mind to date. Using monkeys as his test subjects, he would connect the microelectrodes to the subject’s brain in the area that would respond to sensation in the animal’s hand. Then he would touch the monkey’s hand – over and over, over days to produce a picture of that region of the brain.

Once Merzenich had mental hand maps for his subjects, he did this to six monkeys; he took a scalpel and severed nerves in the hand. Then he returned to monitoring the mind and touching the monkeys’ hands. The signals this time were scrambled. An area he had touched before would respond in a different part of the brain. After months, as the nerves in the hand were repaired, the mental pathways also re-established themselves.

This research would begin the march toward understanding the full neuroplasticity of the brain.

Subsequent studies would show that this reorganization, strengthening, or atrophying can happen throughout one’s lifetime – through small and big changes.

Examples are found in the range of human experience; when a person becomes blind, their visual cortex will re-engineer itself to process sound, stroke victims can regain control over their limbs through repeated training, and musicians' brains show psychical changes as a result of playing their instrument. This is also not limited to physical changes; we can also change our brains just by thinking. Scientists have shown that long-time cab drivers have larger areas of their brains dedicated to spatial mapping and that imagining playing a song on the piano develops the same neural network of connections as actually playing the song.

Philosopher William James suggested a version of this in the 1880s when he mused that we are what we think about and that we are what we give our attention to. Or as Carr writes, “we become, neurologically, what we think.”

Much of the science of neuroplasticity is exciting. Revealing new ways to think, practice, and heal, but it also has a dark side. This feature of our minds can exacerbate mental health disorders. Depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and anxiety can also become inflamed as the affiliated person perseverates more and more on their symptoms. The more they think about their symptoms, the deeper those pathways of their affliction become.

Anything that becomes a habit creates a pathway. The more you do the thing, the stronger the pathway. It’s like running water on rocks; over time, the groves deepen, and eventually, the groves can become like a river in a canyon.

For many of us, especially Gen Z, the deepening pathways have led to increasing mood disorders and mental health problems. The kids are not alright, so to speak—especially the girls. Between the ages of 12-17, major depressive disorders have become a common feature of adolescence and young adulthood. One in four, soon to be one in three, American girls will seek treatment for a major depressive disorder. Visits to the emergency room have exploded. These young patients seek help for suicide attempts, ideation, and cutting behaviors. Incidents that were fairly uncommon just 11 years ago have become a daily feature of our country’s major hospitals.

Professor Dr. Jean Twenge traces the origin of this shift in her insightful book, iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood. Twenge argues and empirically proves that iGen, or kids born after 1995, are being shaped, often for the worse, by the rise of disruptive technology in our lives. She writes:

iGen’ers are scared. Maybe even terrified. Growing up slowly, raised to value safety, and frightened by the implications of income inequality, they have come to adolescence in a time when their primary social activity is staring at a small rectangular screen that can like them or reject them. The devices they hold in their hands have both extended their childhoods and isolated them from true human interaction. As a result, they are both the physically safest generation and the most mentally fragile.

The 1995 marker is important for two reasons; the first is embedded into the word choice of her book title. iGen is named for the young people who are the first generation to be raised through adolescence in concert with the widespread adoption of the iPhone. The iPhone was launched in 2009 but was still fairly expensive, and only a few individuals had one. By 2011, the iPhone was widely available, as well as many other smartphones. This shift toward operating in the world with the Internet in our pockets transformed how we all access information, interact, and, most importantly, see and value ourselves.

The second important feature of the 1995 marker is an understanding of a pre-and post-iPhone way of living. Those born after 1995 often know nothing other than existence connected to the Internet at every moment of the day, making this generation more susceptible to the ills of the always online existence. It is important to note that we are all susceptible to the same ills, compulsions, and addictions generated by these devices and platforms. I am sure many of you may see yourselves in these descriptions. We are all in this together. (In the United States, deaths of despair — suicide, alcoholism, and opioid addiction — across gender and class are currently at an all-time high)

Published in 2016, Twenge offers an array of compelling data in iGen. Compiled through troves of data collected by government bodies over the course of generations, such as Monitoring the Future, as of 2015, 33% of girls between 8th and 12th grade demonstrated depressive symptoms, 31% of 8th through 12th graders often felt lonely, 33% often felt left out, 36% reported that they felt they could not do anything right, 31% reported that they felt their lives were not useful, and 29% reported that they do now enjoy life. In 2016, over 50% of college students reported their emotional health as below average.

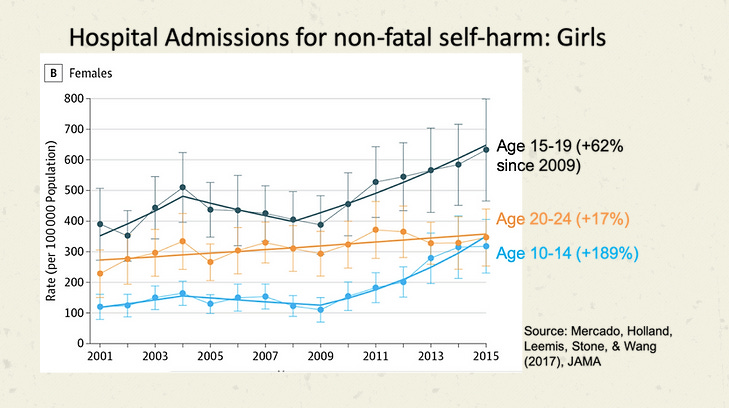

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published similar and supporting data. A data set published in 2015 showed a dramatic increase in hospital admissions for non-fatal self-harm for girls since 2009. For women aged 20-24 years, the rate jumped 17%; for girls aged 15-19 years, 62%; and for girls aged 10-14 years, 189%.

The common theme in all of these graphs is the marker of the year 2011. The statistical elbows explode off the page. In graph after graph, in 2011, the rates jumped, and they have stayed high. As these young people gain access to disruptive technology and spend more time in the alluring pull of their devices, their mental health deteriorates.

But here’s the kicker: all this data was collected before the COVID-19 pandemic. A global experience that forced most of us into our homes and drove many of us, especially the young, deeper into technology. Sadly, and expectantly, the rates of mental health problems have gotten worse. COVID-19 took a mental health fire that had started burning in 2011 and dumped gasoline on it.

I noticed a major shift in my students as we returned to in-person learning following a year of virtual education. The students were more connected to their devices than ever, using them as a security blanket. In one dramatic example, a student with a broken phone sat pretending to scroll, I suspect, as a way to feel safe. As I walked through the halls, the students appeared like lines of digital zombies, scrolling and blindly walking. Sometimes they would sit together in silence, heads down, faces aglow. I had noticed this technological creep over the past decade, but now it seemed to be a ubiquitous way of life.

In June 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics declared a state of emergency in child and adolescent mental health. “During 2020, the proportion of mental health-related emergency department (ED) visits among adolescents aged 12-17 years increased 31% compared with 2019,” the report reads. “In May 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, ED visits for suspected suicide attempts began to increase among adolescents aged 12-17 years, especially girls. During February - March 20, 2021, suspected suicide attempt ED visits were 50.6% higher among girls aged 12-17 years than during the same period in 2019; among boys aged 12-17, suspected suicide attempt ED visits increased by 3.7%.”

Anecdotally, my wife, an emergency room physician treating adult and pediatric patients, saw the same trends in her Level 1 emergency room in St. Louis County. As I did my qualitative research, probing her and her colleagues about their high school-aged patients, their descriptions tracked with the timelines of the data. For the nurses and doctors who had worked in the Emergency Room for more than 12 years, they found that early in their careers, they very infrequently saw young patients coming in for suicide attempts or ideation; after 2011, the trickle became a steady stream, and by 2023, it was an everyday occurrence.

JAMA released a report in October of 2022 written by a group of volunteer health experts who recommended that all kids eight and over be screened for anxiety. And in another first, it also recommended all kids 12 and up get screened for depression by primary care physicians. Presently, almost 6 million children under 17 have anxiety, while suicide is the second-leading cause of death for those between 10 and 19 years old.

The task force report said, “Depression is a leading cause of disability in the US. Children and adolescents with depression typically have functional impairments in their performance at school or work as well as in their interactions with their families and peers. Depression can also negatively affect the developmental trajectories of affected youth. Major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents is strongly associated with recurrent depression in adulthood; other mental disorders; and increased risk for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completion. Psychiatric disorders and previous suicide attempts increase suicide risk.”

These trends are startling. If we trace the growth in negative mental health revealed by Twenge starting in 2011 and pull the line through to the pandemic, we can see how the Internet and social media use for girls is complicit in the decline in mental health.

Girls spend more time on social media than their male peers, who spend a significantly higher portion of their online time playing video games than their female counterparts. Social media appears to be the most insidious culprit in this story, and the current platforms that are the most harmful appear to be Instagram (owned by Meta, formerly Facebook) and TikTok (owned by the Chinese company ByteDance). With Instagram and TikTok, the performative aspect of these platforms mandates a curation of the self, designed for broad public evaluation. They are used as vessels for evaluating self-worth, and Instagram and TikTok focus on evaluating the body more than just the face.

In many ways, these platforms are tapping into an old trap for young women — being valued primarily by their appearance. Girls learn early that the more provocative the image, the more interaction and positive feedback they get. In a culture where ideas of female empowerment have taken center stage, our young females are ceding their self-worth to old tropes. The images in women’s magazines, films, and television that became a feature of modern life in the 20th Century can now follow us everywhere. Many girls are filling every moment of empty time with these images. I would notice students lifting their phones slightly above their heads, tilting and posturing, and snapping hundreds of photos. Applying filters and sharing these images.

Often our gut reaction to these kinds of scenes is to pass judgment. To see these motions as narcissism. And Twenge would, rightfully, argue that we are in a narcissism epidemic (she wrote a book about it). But there is also more to this story. This is also the world these young people have been given. The world they have inherited. This is how American culture tells them they should be evaluated and their worth assessed. These are people trying to figure out how to feel self-confident but are working with a tool that destroys confidence. We need to offer the next generation something better. But to do that, we have to understand our participation in the creation of this system and the passivity with which we have accepted it.

As American parents watch their children slide into this miserable existence, they wonder, “Why is this happening? Why would these companies do this to our children?” The answer, as it often is in American capitalism, is money. They do it because it makes them a lot of f*cking money.

As author and New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino writes in her essay, The I in Internet, published in her 2019 book Trick Mirror, “This system persists because it is profitable. Tim Wu writes in The Attention Merchants that commerce has been slowly permeating human existence — entering our city streets in the nineteenth century through billboards and posters, then our homes in the twentieth century through radio and TV. Now, in the twenty-first century, in what appears to be something of a final stage, commerce has filtered into our identities and relationships. We have generated billions of dollars for social media platforms through our desire—and then through a subsequent, escalating economic and cultural requirement—to replicate for the internet who we know, who we are, and who we want to be. Selfhood buckles under the weight of this commercial importance.”

The Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen revealed these motivations in the internal data she leaked to The Wall Street Journal in their expose, The Facebook Files. The documents revealed that Facebook knew that its platform and products were harmful on various levels – to democracies, to political discourse, the future of our nation, and teens – and continued to prioritize engagement and, thus, profit over more noble aims.

Among the statistics shared by Haugen, and shared by the WSJ, were these gems, “Thirty-two percent of teen girls said that when they felt bad about their bodies, Instagram made them feel worse,” the Facebook researchers said in a March 2020 slide presentation posted to Facebook’s internal message board, reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. “Comparisons on Instagram can change how young women view and describe themselves.” Other internal research showed that Facebook knew they, “Make body image issues worse for one in three teen girls,” said one slide from 2019, summarizing research about teen girls who experience the issues. “Teens blame Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression,” said another slide. “This reaction was unprompted and consistent across all groups.” Among teens who reported suicidal thoughts, 13% of British users and 6% of American users traced the desire to kill themselves to Instagram, one presentation showed.

Essentially, the company’s products are dangerous for young people, and they know it. Still, their desire to suck up more power and money blinds them to the horrors they are causing for families all over America.

In another of Jia Tolentino’s brilliant essays featured in Trick Mirror, entitled 7 Scams that Define a Generation, she writes, “What began as a way for Zuckerberg to harness collegiate misogyny and self-interest has become the fuel for our whole contemporary nightmare, for a world that fundamentally and systematically misrepresents human needs … at a basic level, Facebook, like most other forms of social media, runs on doublespeak - advertising connection but creating isolation, promising happiness but inculcating dread.”

As our nation’s teens endlessly scroll TikTok and Instagram, they are sinking deeper into despair. Seeking comfort in a technology designed primarily to commodify their attention, they find no comfort at all. Briefly, it quiets the compulsion while carving a deeper pathway in the brain for addiction. As the age of children who have smartphones continues to shift younger each year, we open up their brains to more time for their mental habits to be hijacked and shaped by the purveyors of products interested in manipulating the mind for money.

Tristan Harris, executive director and co-founder of the Center for Human Technology, who left his job at Google due to ethical concerns about the products the tech industry was building, describes how the business models of the industry are founded on promoting damaging manipulation for profit, “Just like war is good for GDP, suicidal ideation in girls is good for Facebook and for Instagram, alienation, and body image issues are good for Instagram and good for engagement,” Harris said in a Bloomberg interview following The Wall Street Journal’s release of Haugen’s Facebook Files. Harris views this race for attention as the race to the bottom of the brain stem.

So what do we do? How do we resist? How do we push back in a culture where it feels that these technologies have come to invade every facet of our lives?

The first step is to wake up from the passivity which we have accepted so that we can demand something better.

Johann Hari’s new book Stolen Focus (a must read) offers us a wake-up call through a conversation with political writer Naomi Klein.

Klein observes that the pandemic actually offered us an opportunity.

“We were on a gradual slide into a world in which every one of our relationships was mediated by platforms and screens, and because of COVID, that gradual process went into hyper-speed,” Klein said (according to Hari, in April 2020, the average US citizen spent 13 hours a day looking at a screen). “The plan was not for it to leap in this way … the leaping is an opportunity, really — because when you do something that quickly, it comes as a shock to your system.”

That shock is our chance to open the door to a different future than the one the tech industry had planned for us. We don’t have to succumb to the wishes of the toolmakers, and we do not have to blindly follow the path of progress if that progress is actually a regression — a stunting of our societal intellect, a stunting of meaningful human interaction, a stunting of the experiences that lead to living the good life. We can shape our tools to meet our requirements and stop adapting ourselves.

Keep looking for connection,