Could I interest you in everything?

All of the time?

A little bit of everything

All of the time

Apathy's a tragedy

And boredom is a crime

Anything and everything

All of the time

Bo Burnham, Welcome to the Internet

If you have not yet watched Bo Burnham’s musical comedy Inside, which he produced alone during the pandemic, you are missing out on one of the great cultural philosophers of the 21st Century.

Burnham is a comedian by trade, but he is much more than a funny man. He is an acute observer of how our lives are lived, valued, and devalued through digital compression.

His song, Welcome to the Internet, engages what I believe are the fundamental underpinnings of why the Internet degrades our collective thinking.

First, it is because the Internet is a little bit of everything all of the time.

And everything it really is. So much, in fact, that we resort to taking in little bits with the hope of covering as much material as possible. Skimming vast amounts of information at the surface.

Sune Lehmann, a professor in the Department of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science at the Technical University of Denmark, wondered about his own deteriorating ability to focus and decided to study if our collective attention spans were deteriorating.

First, Lehmann started with an analysis of eight years of Twitter data to determine if the time a topic trended on the platform was being compressed. In fact, it was. It 2013 a topic trended on Twitter for 17.5 hours, whereas three years later, that number dropped to 11.9.

So Lehmann and his team decided to apply the same methodology to a variety of content pools — Reddit, films, Google searches, etc. In all the content pools, they found the same result—the length of time our collective attention focused on any topic was reducing rapidly.

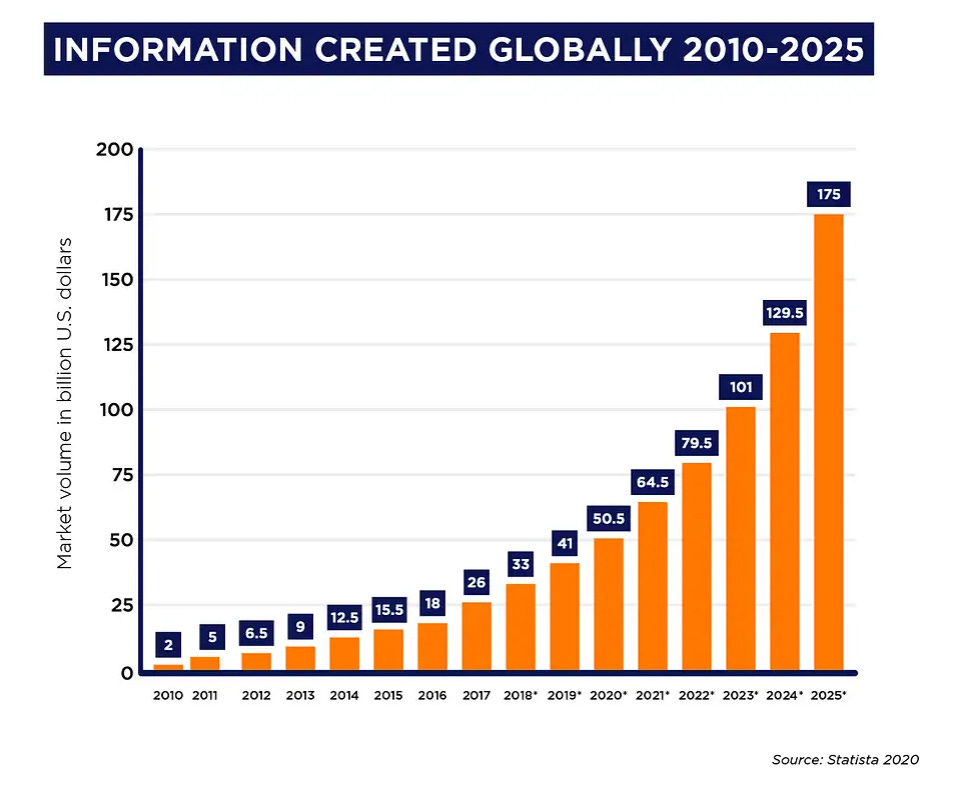

Next, Lehmann turned to Google books. Using an analysis of text uploaded to Google books from the 1880s to the present, the team found that this acceleration in topics has been happening for the last several generations and that the rate of change keeps getting faster and faster. Each new inflection of rate change appeared to correlate with growth in information delivery and distribution systems.

Author Johann Hari puts it this way, “You just have to flood the system with more information. The more information you pump in, the less time people can focus on any individual piece of it.”

Hari points to a study by professors Dr. Martin Hilbert and Dr. Priscilla Lopez that shows in 1986, the amount of new information being produced (TV, newspapers, magazine, etc.) being pumped at the average person a day was about 40 newspapers worth of information, by 2007, that number of 174.

So we skim a vast amount of information, but we are floating at the surface rather than exploring any one topic deeply because depth takes time, attention, and reflection.

Apathy's a tragedy, And boredom is a crime.

This is the second underpinning for why the Internet is bad for our collective thinking. The design of most of the sites we engage with manipulates our emotions while simultaneously making us dopamine addicts.

This is done on purpose. Because boredom is good for thinking, and the purveyors of these technologies don’t want us to think about how we are spending our time, because if we came up for air long enough to really think about it, we might make a different choice.

The philosopher Bertrand Russell described the virtue of boredom in his 1930 book The Conquest of Happiness in a chapter entitled “Boredom and Excitement.”

We are less bored than our ancestors were, but we are more afraid of boredom. We have come to know, or rather to believe, that boredom is not part of the natural lot of man, but can be avoided by a sufficiently vigorous pursuit of excitement.

…

I do not mean that monotony has any merits of its own; I mean only that certain good things are not possible except where there is a certain degree of monotony… A generation that cannot endure boredom will be a generation of little men, of men unduly divorced from the slow processes of nature, of men in whom every vital impulse slowly withers, as though they were cut flowers in a vase.

…

The special kind of boredom from which modern urban populations suffer is intimately bound up with their separation from the life of Earth. It makes life hot and dusty and thirsty, like a pilgrimage in the desert. Among those who are rich enough to choose their way of life, the particular brand of unendurable boredom from which they suffer is due, paradoxical as this may seem, to their fear of boredom. In flying from the fructifying kind of boredom, they fall prey to the other far worse kind. A happy life must be to a great extent a quiet life, for it is only in an atmosphere of quiet that true joy can live.

We’re Already Living in the Metaverse

Megan Garber’s recent cover story in The Atlantic brings the receipts of our cultural slide away from tolerance of boredom toward a life that is all about staying entertained.

Garber’s thesis considers while many of us have perseverated about a kind of authoritarian dystopian future in the mold of 1984, Fahrenheit 451, or a Brave New World, that perhaps, the real warning came from the writer Neil Postman. In his 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, Postman warned that a culture that relentlessly demands to be entertained could also slide into chaos through confusion.

Postman saw a public that confused authority with celebrity, assessing politicians, religious leaders, and educators according not to their wisdom, but to their ability to entertain. He feared that the confusion would continue. He worried that the distinction that informed all others—fact or fiction—would be obliterated in the haze.

…

Dwell in this environment long enough, and it becomes difficult to process the facts of the world through anything except entertainment. We’ve become so accustomed to its heightened atmosphere that the plain old real version of things starts to seem dull by comparison. A weather app recently sent me a push notification offering to tell me about “interesting storms.” I didn’t know I needed my storms to be interesting. Or consider an email I received from TurboTax. It informed me, cheerily, that “we’ve pulled together this year’s best tax moments and created your own personalized tax story.” Here was the entertainment imperative at its most absurd: Even my Form 1040 comes with a highlight reel.

Such examples may seem trivial, harmless—brands being brands. But each invitation to be entertained reinforces an impulse: to seek diversion whenever possible, to avoid tedium at all costs, to privilege the dramatized version of events over the actual one. To live in the metaverse is to expect that life should play out as it does on our screens. And the stakes are anything but trivial.

Being Human

The most important question that faces us as a collective, thinking society—if we want to retain this kind of agency—is, “How do we interact with the Internet in a way that retains our humanity?”

Maybe, first, we need to remind ourselves what it means to be human in the first place and what it means to be alive without the Internet. I turn to the wisdom of Walt Whitman for such an answer.

Late in his life, Whitman suffered a stroke that psychically disabled him but left his cognition as sharp as ever. For Whitman, the effect of the stroke also fostered a chance to reflect on the quality of his life, which he did in Specimen Days.

What mentality I ever had remains entirely unaffected; though physically I am a half-paralytic, and likely to be so, long as I live. But the principal object of my life seems to have been accomplish’d — I have the most devoted and ardent of friends, and affectionate relatives — and of enemies I really make no account.

…

The trick is, I find, to tone your wants and tastes low down enough, and make much of negatives, and of mere daylight and the skies.

…

After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, love, and so on — have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear — what remains? Nature remains; to bring out from their torpid recesses, the affinities of a man or woman with the open air, the trees, fields, the changes of seasons — the sun by day and the stars of heaven by night.

If we want to return to our humanity it is essential we reorient our scale of self. Instead of measuring ourselves through the portal of our devices—where profiles and engagement expand the neediness of our ego—the solution is to find spaces that make us feel humble and small. Spaces that remind us of the real scale of our lives. Spaces that allow us to focus on one thing at a time, not a little bit of everything all of the time. Spaces that allow us to feel a sense of calm. Spaces that allow us to be bored.

____________________

Thanks for reading! If you made it this far, and you’ve been enjoying Missives from a Luddite, please pass it on to a friend or two who you think might enjoy it too.

Best, Erin