The Three Chairs

The United States is in a loneliness epidemic. Researchers Sherry Turkle, Robert Waldinger, Marc Schulz, and John Gottman offer us lessons for reclaiming what matters most.

“I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.”

-Henry David Thoreau, Walden

My previous two posts focused on setting the frame of our cultural struggles as we allow our technological tools to transform us; this piece is about solutions. The first of those solutions is the healing power of conversation.

In his recent book Stolen Focus, author Johann Hari lays out how social media distorts reality, harms our attention, and makes us susceptible to narrow and sometimes obsessive thinking. First, he says the apps are designed to make users crave rewards. Using B. F. Skinner's famous psychological research on behavior, tech designers trained at Standford’s Persuasive Technology Lab have turned users into the equivalent of rats, chasing likes and comments.

Using an intermittent reward response, tech merchants hook us on their products. In Skinner’s studies, if a rat gets a reward every time it presses the lever, or never when it presses the lever, it chills out on the lever pushing. However, when the reward is intermittent, the rats go crazy for the lever. That is social media. Sort of unsatisfying most of the time, but every once in a while pretty cool. It is designed to keep us coming back for more.

In my observations and discussions with students, I found it’s fairly easy to turn users into social media rats who find it difficult to get off the hamster wheel of reward-seeking. My students would tell me how they would wait until a certain time of day, typically in the evening, when they knew most of their peers would be on social media to post an image to maximize the number of likes. If the image did not break a certain threshold, say 100 likes, they would take the post off their social media feed to save face. They didn’t want anyone to know if they had posted a dud.

Students would describe how they felt they were always on, engaged in a performance. They also knew that their posts were curated versions of their lives and did not reflect who they really were. They knew that someone was not a “friend” just because they liked an image, but they couldn’t look away, and they couldn’t help obsessively wondering why so and so hadn’t liked their image yet. Did it mean that they weren’t friends anymore?

What is a friend anyway? This turns out to be one of the essential questions for living a good life.

MIT Professor Dr. Sherry Turkle probes this question and others like it in her 2015 book Reclaiming Conversation.

In the work, Turkle uses the framing of Henry David Thoreau and the three chairs as the architecture for her argument. Thoreau had three chairs in his cabin in the woods — one was for solitude, the second for friendship, and the third for society. Turkle contends that our relationship to technology in the 21st Century disrupts our ability to attend to any of these three chairs well.

Today, I will focus on the first two chairs as the starting blocks to living a life of meaning and purpose.

The first chair, solitude, or the joy of being alone, is increasingly hard to find. Our personal content companions now disrupt the quiet moments we once held open for solitude. I find that many people fill that quiet space as a compulsion. When we have a pang of boredom, we seek to fill it as quickly as possible with input — so we don’t let ourselves feel discomfort, solitude, or boredom. But boredom is good for thinking. Moments of solitude are how our unconscious mind builds connections and retrieves information which sparks creative thinking.

Many of my students described checking their phones as a way to calm their anxiety. These young people were calming their anxiety with a product that makes people more anxious—creating an endless loop. As we fill every quiet moment with content, we disrupt our capacity for self-reflection. Turkle’s contention is that without self-reflection, without the ability to be in solitude (to feel joy in being alone), we become incapable of fully entering the spaces of friendship and society.

The brilliant writer Jia Tolentino says it this way:

“The internet is governed by incentives that make it impossible to be a full person while interacting with it. In the future, we will inevitably be cheapened. Less and less of us will be left, not just as individuals but also as community members, as a collective of people facing various catastrophes. Distraction is a life-and-death matter,” Jenny Odell writes in How to Do Nothing. “A social body that can’t concentrate or communicate with itself is a like a person who can’t think and act.”

The chair of friendship. Turkle’s chair of friendship represents three kinds of relationships — friendships, family, and romantic relationships. All three, she argues, are diminished by the appearance of the smartphone. Her research shows that simply having a phone present hinders where a conversation might flow — it subconsciously suggests to your conversation partner, “I am here for now until something better comes along.”

We need to be better with the people that are important to us. We are all susceptible to taking the people we love and who love us for granted. This complacency has become an even easier slide with lives lived frenetically and distractedly. Where melting into the couch, double screening with Netflix and our iPhone feels like a good response to the overload.

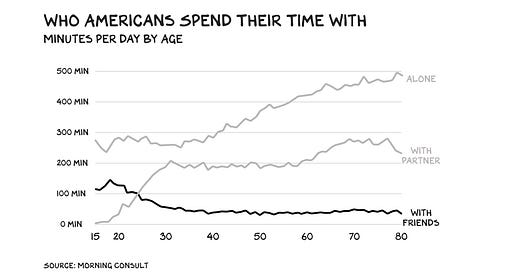

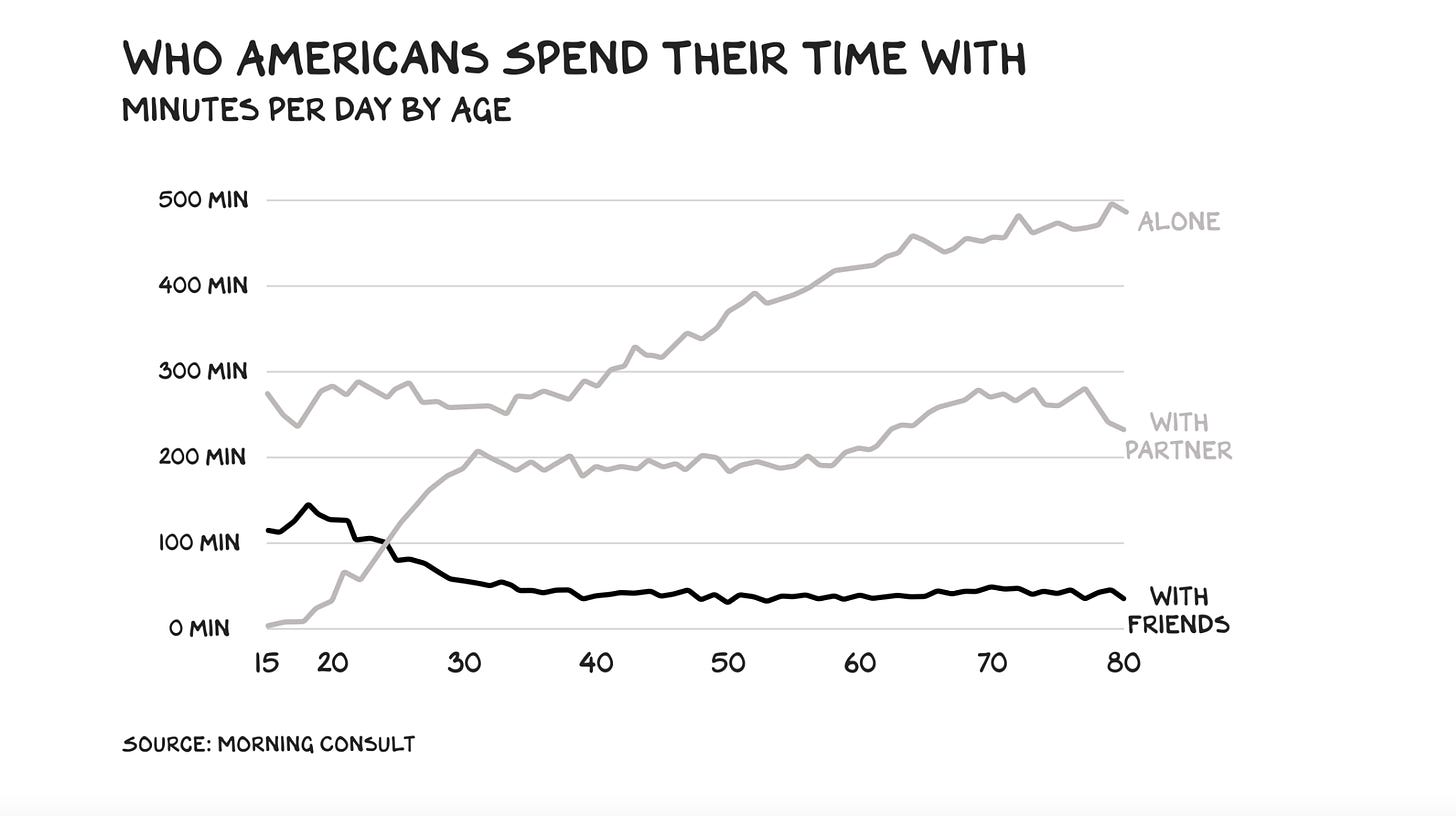

On average, Americans spend about two and a half hours on social media every day.

What if instead of spending time scrolling through feeds of digital friends, we spent that time each day seeing a friend in person (in real life, as they say)? Or talking to a friend on the phone? Voice to voice.

According to Professor Noreen Hertz, author of The Lonely Century: How to Restore Human Connection in a World That's Pulling Apart, the data shows a dramatic decrease in the number of close friends people say they have and an equally dramatic increase in our rates of loneliness. In the United States, three out of every four adults reported moderate to high levels of loneliness.

Another recent book provides the antidote to this trend. The Good Life: Lessons from the World's Longest Scientific Study of Happiness by Dr. Robert Waldinger and Dr. Marc Schulz unpacks the longest study of human happiness ever conducted. It reminds us why investing in relationships is the most important thing we can do to live meaningful, satisfied, purpose-filled lives. Waldinger and Schulz found that the keys to living the good life were (1) taking care of our physical bodies and (2) the quality of our relationships.

The physical body part, of course, makes a lot of sense. Exercise, eat well, get good sleep, avoid drugs, and don’t drink too much. If you do these things consistently, you will have more satisfaction throughout your day and enjoy life more.

The relationships part is where it gets especially interesting. On some level, we know this. Having deep and meaningful connections to other people matters more than anything in our lives. But it turns out that these relationships are not just important on a psychological level; they are also important on a biological level. Having meaningful relationships actually changes our physical bodies. According to NYU professor Scott Galloway, '“Loneliness registers an impact on your well-being similar to that of smoking 15 cigarettes a day and rivals alcohol and smoking as a cause of early death.” Loneliness increases inflammation, heart disease, dementia, and death rates.

Loneliness has become such a problem in the 21st Century that in 2019 (a year before the pandemic), the UK appointed a “minister for loneliness.”

According to a Survey Center on American Life study, the number of Americans who report having no close friends has quadrupled since 1990. In 2021, US citizens spent 58 percent less time with friends than eight years before.

So we want to avoid being lonely. But then the questions become — what kind of relationships are most important? How many do you need? How do we know who is a “friend” these days? This is can be a confusing idea in the 21st Century when a “friend” can be easily confused with someone who likes or comments on a curated version of a life that has been put on the Internet for public performance.

Waldinger and Schulz found that strong and weak ties are important to overall life satisfaction. Weak ties are the people we have in our lives that we see on occasion that we enjoy bumping into and chatting with. Maybe it is a neighbor on your street, the person that works at the local coffee shop, or the parent you see at pick-up. These relationships are important to round out the variety of our lives, and, more importantly, they make us feel like we are part of a community. Weak ties make us feel as though we are connected to a broader network of support and belong to something bigger than ourselves.

Strong ties, of course, are the most important. To determine who is a strong tie, Waldinger and Schulz suggest asking yourself, “Who could I call and say, ‘I’m in trouble, I need help,’ and that person would drop anything and be there for you?” According to Waldinger and Schulz, you need at least one person in your life that fits this bill. If you have a few more, even better. However, the researchers found that many people could not offer one name, even if they were married.

I’ve been lucky to have several of these kinds of friendships in my life. In many ways, I credit abstaining from social media for the last year or so with deepening those relationships. My friendships have never been richer and more meaningful (nor has my thinking ever been clearer).

In families, studies show parents increasingly pay more attention to their phones than their children and, as a result, miss opportunities to help their children develop vital interpersonal skills through the art of conversation. Conversation with family is a space where you don’t have to be perfect; you don’t have to get everything right; you get to come back, day after day, and try again.

Turkle writes, “Relationships deepen not because we necessarily say anything in particular but because we are invested enough to show up for another conversation. In family conversations, children learn that what can matter most is not the information shared but the relationships sustained. It is hard to sustain those relationships if you are on your phone.”

“I tweet. Therefore, I am.” Social media, on the other hand, teaches something very different. It is a performance medium. It is a stage. You are not there to listen, develop empathy, or understand others; you are there to broadcast the most tailored version of yourself.

It is essential that parents show up for their children undistracted to teach them about the importance of sustained, considered conversation. We all want our children to grow up to have happy and meaningful lives. If we want that for them, we need to model that real friendships, real relationships, require in-person conversation — that what happens in real life is most important for building meaningful connections.

The presence of our devices also hinders romantic relationships. Because when we turn toward our smartphones and away from our partners, we diminish the foundation of our relationship. It is small acts that make all the difference.

The wonderful work of John Gottman shows that there is nothing more important for sustaining a long-term relationship than responding to bids for attention. Gottman can predict with over 90% accuracy whether or not a couple will stay married within five years based on how the couple responds to one another’s bids for attention. Gottman and his research partner Robert Levenson brought couples into “The Love Lab” (an apartment with cameras installed for recording interactions). The researchers recorded the couple discussing their relationships and disagreements, and followed them as they spent a week interacting in “The Lab.” They followed up with those couples six years later to see who was still married and whether they were happy.

In John Gottman’s book the “The Relationship Cure“, he writes, “After many months of watching these tapes with my students, it dawned on me. Maybe it’s not the depth of intimacy in conversations that matters. Maybe it doesn’t even matter whether couples agree or disagree. Maybe the important thing is how these people pay attention to each other, no matter what they’re talking about or doing.”

Building a healthy relationship depends on how we respond to our partner’s bids for connection. The “masters,” as Gottman called them, responded to their partner’s bids for attention 86% of the time, whereas the disasters responded 33% of the time.

Like all relationships, this is a work in progress. Some days we are better than others. Some days we hit our target, and some days we fall short. I have been blessed with a wonderful, supportive partner who tries daily to attend to our relationship. Who recognizes the importance of small acts, which grow into large reserves of trust and companionship over time.

If we want meaningful relationships, the key to living the good life, we need to put down our phones, take the time we get back, and invest it in our friends, families, and partners.

And we do have the time; it is just being stolen — now is the time to reclaim it.

Keep looking for connection,

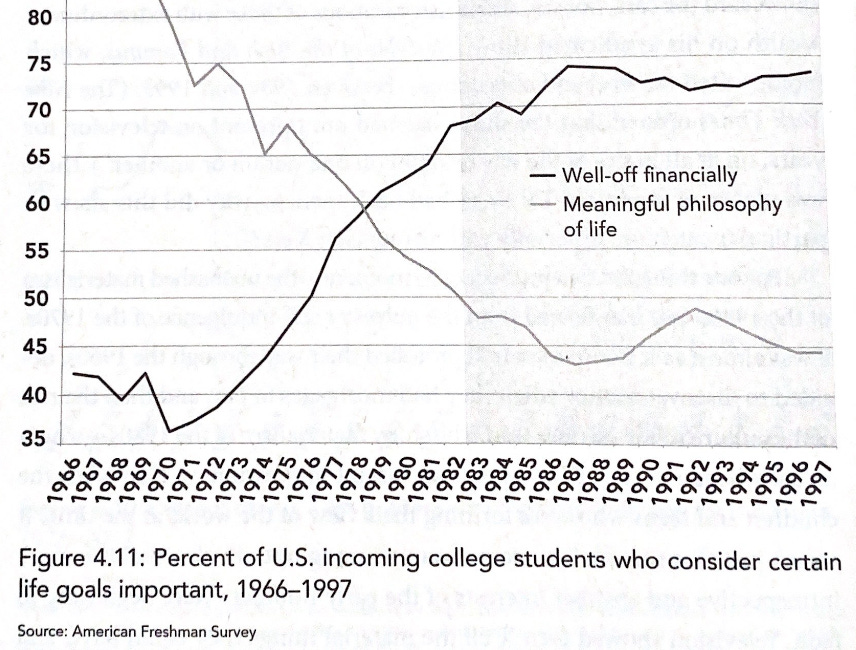

A Meaningful Philosophy of Life

I am coming up on another birthday. I like milestones. Markers of time that call you to take inventory. What you’ve tackled. Or survived. What brought you joy. What brought you sorrow. And how best to apply that learning to the next year — in hopes that there is more joy than sorrow for the next trip around.